Distributions

Distributions of data are one of the first things you should look at, especially if you have large sample sizes. Think mini amplitude, IEI, and rise rate. Most the statistical analyses we use make assumptions about the distribution of our data yet rarely do papers show distributions of their data. Part of this is because most papers just average per mouse or per cell or they have a small N which makes it hard to determine the distribution of points. In this section we will cover some ways to understand the distribution of your data even for small sample sizes and how to visualize your data. We will also cover what a distribution is and cover some distributions I think that you should know.

Distributions can show counts or probabilities. When you make a histogram or kernel density estimate (KDE) you are creating a distribution of your data (technically a non-parametric distribution). Most often in statistical text books you will see something called probability density functions (PDF) for continuous variables or probability mass functions (PMF) for discrete variables. These are parametric distributions becuase that have parameters that describe the distribution. The important thing about these “functions” is that the distribution of values you get from the functions integrates (i.e. the area under the curve) to 1 for the when you take the distribution from negative limit to positive limit. When you put in a single number with some parameters you get a number out called a likelihood.

The last thing to note is that finding the distribution that fits your data describes your data but does not tell you how or why it was generated that way. The how and why questions are not something we will get at here and are what computational neuroscientists study.

You will also often see cumulative distribution functions (CDFs). The CDF is the just the integral of the PDF and the PDF the derivative of the CDF. When taking the integral of a continous function you can just use a Numpy cumsum and multiply by your delta X to get the CDF if you have evenly spaced samples. For the area under the curve you can use a variety of functions provided by scipy such as the trapezoid, simpson, or the romberg. Below we will plot the PDF and CDF for each of the distributions.

For this tutorial, there are interactive samples. Not all of these examples use the preferred way of working with distributions in Python. The recommended way is to use the Scipy stats module. The stats module distrbutions provide a lot of useful features but can be a little bit intimidating to start with. Scipy stats distributions can provide PDF/PMFs, CDFs, PPFs and fit distributions to your data using maxmimum likelihood.

If you want to learn a little more about PDFs and PMFs I suggest watching Very Normal on Youtube.

First we are going to cover some terminology then we look over some of the data we tend to collect in electrophysiology experiments and see what the distribution of data looks like. Finally we are going to go over some specific distributions and see which distributions look most like our data.

Terminology¶

For all the terminology we assume that the x-axis are real numbers and the y-axis is probability/likelihood. Remember that distributions show the probability/likelihood of getting a value. The value is on the x-axis and the probability/likelihood is on the x-axis. Most distributions taken a location, shape or scale parameter or some combination of the three.

Location¶

Location can be thought of as an additive parameter that shifts the distribution along the x-axis without changing is shape. For example a normal distribution equation specifies a distribution with mean 0. If we draw random values from the distribution they will tend to have mean 0 but we can shift the mean by just adding the same value to all the values. If we shift the location of the normal distribution then we change the mean. Very few distributions naturally support a location parameter of which the normal distribution is one. The location of distribution is very important in biology because we are often testing to see whether there is a location shift between groups. When we start to get data with non-normal distributions we cannot test for location shifts unless you use specialized statistical packages or transform the data.

Scale¶

Scale relates to the range of values you are likely to get from the distribution. For the normal distribution scale is the standard deviation. Scale is important in many non-normal distributions as well.

Shape¶

The shape interactions with scale to modify how a distribution looks. It is wide, or narrow, skewed right or left. Shape is a parameter used by many non-normal distributions. It will change the central tendency (most common value) of the distribution but not in the way location does.

Skew¶

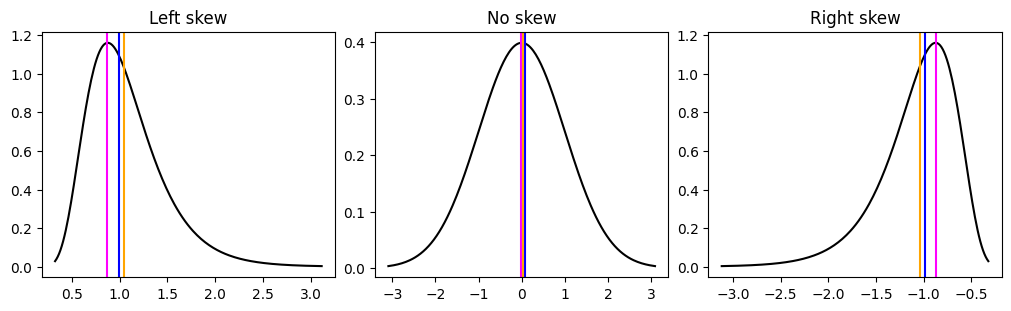

Skew is whether the distribution tends have higher likelihood for low values vs high values or vice versa. Skew is not a parameter that goes into a parameterized distribution but a desciption of a distribution. Shape and scale often interact to change a distribution’s skew.

Kurtosis¶

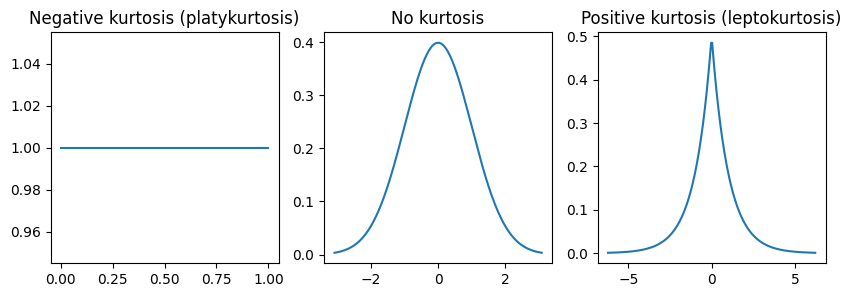

Kurtosis is the tailedness of the distribution. Long tailed distributions increase the likelihood of getting extreme values. Shape and scale often interact to change a distribution’s kurtosis.

Source

import math

import warnings

from pathlib import Path

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from bokeh.io import output_notebook, show

from bokeh.layouts import column, row

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource, CustomJS, Select, Slider, Whisker

from bokeh.plotting import figure

from scipy import stats

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", category=RuntimeWarning)

cwd = Path.cwd().parent / "data/pv"

df = pd.read_csv(cwd / "mini_data.csv")

output_notebook()Examining distributions in your data.¶

The most common method to look at distributions of data is to use a histogram, KDE (note: violin plot is just a KDE) or the box plot. My preferred method is to use a kernel density estimate (KDE). All these methods are non-parametric in that they technically do not have any parameters other than your data to create a distribution. The reason I prefer KDEs to histograms is that you can interpolate where you do not have data. Boxplots are an extremely simplified distribution that uses precentiles to deccribe the distribution. KDEs are essentially the non-parametric probabability density function like the ones we already covered. I will show you how create a histogram and KDE in Python and then we will use the KDE to compare our data to the distributions above.

There are a couple things you should look for in your data.

What are the bounds? Are -infinity to infinity, 0 to 1, 0 to infinity? Data that is bounded is often not normally distributed.

Is there a skew to your data? You should take note if your distribution has a long tail to the right (right skew) or a long tail to the left (left skew).

Is there peakness to your data? If the data seems to have a sharp peak or a flat top then you likely have some kurtosis in your data.

How to Create a Histogram¶

To create a histogram in Python the easiest way is to use Numpy’s histogram. For this example we will use 50 bins, however Numpy has a pretty good algorithm for automatically selecting bins. One setting we will use is the density equals true. This will ensure that each bin shows the likelihood so that is matches with the KDE. If you just want to plot a histogram in other popular plotting packags such as Matplotlib or Seaborn, they have modules where you can just put in your data.

def hist(data):

hist, edges = np.histogram(

data, range=(data.min() - 1e-6, data.max() + 1e-6), density=True, bins=50

)

return hist, edgesHow to Create a Kernel Density Estimate (KDE)¶

To create a KDE in Python we are going to use Scipy’s gaussian_kde. There are other implementations of KDEs such Scikit Learn and KDEpy.

KDE stands for Kernel Density Estimate. KDE is a non-parametric density function. There is no predefine function to create the PDF from your data, you create a unique one from your data. The aim of the KDE is not to represent the density function of your data exactly as it is, like a histogram but, to represent it as if you had an infinitely large sample size. KDEs can represent your data as it is by setting a feature called the bandwidth. The only real subjective feature of a KDE is how much to “smooth” your probability distribution that the KDE outputs.

The KDE works by essiantially putting a gaussian distribution (or other distribution) around each point of data and then sums them up. Depending on how smooth we want the distribution we can increase or decrease the bandwidth. For the gaussian distribution the bandwidth is related to the standard deviation. The larger the bandwidth the smoother the KDE and vice versa. There are some algorithms to precompute the bandwidth called Silvermans, Scotts and Improved Sheather-Jones (ISJ) if you don’t want to compute the bandwidth yourself however, Scipy does not provide the ISJ algorithm. There are also different ways to compute the KDE such tree and FFT.

def kde(data):

min_val = min(data)

max_val = max(data)

padding = (max_val - min_val) * 0.1 # Add 10% padding

grid_min = min_val - padding

grid_max = max_val + padding

grid_min = max(grid_min, 0)

positions = np.linspace(grid_min, grid_max, num=248)

kernel = stats.gaussian_kde(data)

y = kernel(positions)

return positions, yHow to create a box plot¶

A box consists of a box that goes from the 0.25 quartile to the 0.75 quartile. There is a line in the middle that is the 0.5 or median. There are whiskers that can be plotted one of two ways. One way is to use the interquartile range (IQR) as is or you can calculate use the minimum point that is closest to the IQR which is useful if the IQR goes beyond any values in your data.

def box(data):

q1, q2, q3 = np.quantile(data, q=[0.25, 0.5, 0.75])

iqr = q3-q1

upper = q3+1.5*iqr

lower = q1-1.5*iqr

wiskhi = data.loc[(q3 <= data) & (data <= upper)]

wiskhi = [q3 if len(wiskhi) == 0 else wiskhi.max()]

wisklo = data[(lower <= data) & (data <= q1)]

wisklo = [q1 if len(wisklo) == 0 else wisklo.min()]

return q1, q2, q3, wiskhi, wisklo

Below we will process all the data.

Source

box_dict = {}

kde_dict = {}

hist_dict = {}

columns = [

"Est Tau (ms)",

"Rise Time (ms)",

"Rise Rate (pA/ms)",

"Amplitude (pA)",

"IEI (ms)",

]

for i in columns:

data = df[i]

if i == "IEI (ms)":

data = data[data > 0]

for f, n in [(lambda x: x, "identity"), (np.sqrt, "sqrt"), (np.log10, "log")]:

q1, q2, q3, wiskhi, wisklo = box(f(data))

box_dict[f"{i}_q1_{n}"] = [q1]

box_dict[f"{i}_q2_{n}"] = [q2]

box_dict[f"{i}_q3_{n}"] = [q3]

box_dict[f"{i}_u_{n}"] = wiskhi

box_dict[f"{i}_l_{n}"] = wisklo

positions, y = kde(f(data))

kde_dict[f"{i}_x_{n}"] = positions

kde_dict[f"{i}_y_{n}"] = y

hist_data, edges = np.histogram(

data, range=(data.min() - 1e-6, data.max() + 1e-6), density=True, bins=50

)

hist_dict[f"{i}_hist_{n}"] = hist_data

hist_dict[f"{i}_left_{n}"] = edges[:-1]

hist_dict[f"{i}_right_{n}"] = edges[1:]

box_dict["q1"] = box_dict["Amplitude (pA)_q1_identity"]

box_dict["q2"] = box_dict["Amplitude (pA)_q2_identity"]

box_dict["q3"] = box_dict["Amplitude (pA)_q3_identity"]

box_dict["u"] = box_dict["Amplitude (pA)_u_identity"]

box_dict["l"] = box_dict["Amplitude (pA)_l_identity"]

kde_dict["kde_y"] = kde_dict["Amplitude (pA)_y_identity"]

kde_dict["x"] = kde_dict["Amplitude (pA)_x_identity"]

hist_dict["left"] = hist_dict["Amplitude (pA)_left_identity"]

hist_dict["right"] = hist_dict["Amplitude (pA)_right_identity"]

hist_dict["hist_y"] = hist_dict["Amplitude (pA)_hist_identity"]Examining the data¶

Below are some plots of our data. There are three common transforms; sqrt, log10 and the negative inverse. These transforms are used to correct for right-skew in your data. The functions correcting for skewness go from light correction to heavy correction in this order: sqrt → log10 → negative inverse. You can also see that since we do not transform the data before any corrections the histogram can look pretty weird. Part of not correcting the histogram before is due to limitations of how this book is written and published. However, you can see how the transform “resizes” the bins, putting greater emphasis (larger bin size) on smaller values. All these transforms decrease the effects of outliers. Additionally, I also plot the mean, median and mode. These are all measures of central tendency. You can see how the transform shifts the mean and median towards the mode. However the mean, median and mode almost never fully align. This is because we have truncated distributions in addition to skew.

Source

menu = Select(title="Variables", value="IEI (ms)", options=columns)

kde_source = ColumnDataSource(kde_dict)

hist_source = ColumnDataSource(hist_dict)

box_source = ColumnDataSource(box_dict)

transform = Select(

title="Transform",

value="identity",

options=["identity", "sqrt", "log"],

)

hist_figure = figure(height=200, width=250, title="Histogram")

hist_data = hist_figure.quad(

top="hist_y",

bottom=0,

left="left",

right="right",

line_color="white",

alpha=0.5,

source=hist_source,

)

kde_figure = figure(height=200, width=250, title="KDE")

line = kde_figure.line(x="x", y="kde_y", source=kde_source, line_color="black")

box_figure = figure(height=200, width=250, title="Box", y_range=(box_source.data["l"][0]*0.8, box_source.data["u"][0]*1.1))

whisker = Whisker(base=0, upper="u", lower="l", source=box_source)

whisker.upper_head.size = whisker.lower_head.size = 20

box_figure.add_layout(whisker)

box_figure.vbar(0, 1, "q2", "q3", source=box_source, color="orange", line_color="black")

box_figure.vbar(0, 1, "q1", "q2", source=box_source, color="orange", line_color="black")

central_tendency = {}

for i in columns:

data = df[i]

if i == "IEI (ms)":

data = data[data > 0]

index = kde_source.data[f"{i}_y_identity"].argmax()

central_tendency[f"{i}_identity"] = [

np.mean(data),

np.median(data),

kde_source.data[f"{i}_x_identity"][index],

]

sqrt_data = np.sqrt(data)

index = kde_source.data[f"{i}_y_sqrt"].argmax()

central_tendency[f"{i}_sqrt"] = [

np.mean(sqrt_data),

np.median(sqrt_data),

kde_source.data[f"{i}_x_sqrt"][index],

]

log_data = np.log10(data)

index = kde_source.data[f"{i}_y_log"].argmax()

central_tendency[f"{i}_log"] = [

np.mean(log_data),

np.median(log_data),

kde_source.data[f"{i}_x_log"][index],

]

central_tendency["x"] = central_tendency["Amplitude (pA)_identity"]

central_tendency["color"] = ["orange", "blue", "magenta"]

central_tendency = ColumnDataSource(central_tendency)

vspans = kde_figure.vspan(x="x", color="color", source=central_tendency)

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

hist_source=hist_source,

kde_source=kde_source,

box_source=box_source,

box_figure=box_figure,

central_tendency=central_tendency,

menu=menu,

transform=transform,

),

code="""

hist_source.data.hist_y = hist_source.data[`${menu.value}_hist_${transform.value}`];

hist_source.data.left = hist_source.data[`${menu.value}_left_${transform.value}`];

hist_source.data.right = hist_source.data[`${menu.value}_right_${transform.value}`];

kde_source.data.kde_y = kde_source.data[`${menu.value}_y_${transform.value}`];

kde_source.data.x = kde_source.data[`${menu.value}_x_${transform.value}`];

central_tendency.data.x = central_tendency.data[`${menu.value}_${transform.value}`];

box_source.data.q1 = box_source.data[`${menu.value}_q1_${transform.value}`];

box_source.data.q2 = box_source.data[`${menu.value}_q2_${transform.value}`];

box_source.data.q3 = box_source.data[`${menu.value}_q3_${transform.value}`];

box_source.data.u = box_source.data[`${menu.value}_u_${transform.value}`];

box_source.data.l = box_source.data[`${menu.value}_l_${transform.value}`];

box_figure.y_range.start = box_source.data.l[0] - box_source.data.l[0] * 0.5

box_figure.y_range.end = box_source.data.u[0] * 1.1

central_tendency.change.emit();

kde_source.change.emit();

hist_source.change.emit();

box_source.change.emit();

""",

)

menu.js_on_change("value", callback)

transform.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(row(menu, transform), row(hist_figure, kde_figure, box_figure)))Gaussian distribution¶

In terms of data that we collect in electrophysiology the gaussian distribution is actually not that common but most of the time we assume our data follows a gaussian distribution. Some non-gaussian distributions, such as the beta and von Mises (radians) distributions, can coverge to a normal distribution with certain parameters. The are problem when you assume that non-gaussian data follows a gaussian distribution AND you do not check your statistical models. We will cover some of this later in this chapter. The gaussian distribution has two parameters, the mean and standard deviation. The mean is what is called a location parameter and shifts the distribution around. The standard deviation is related to the spread of data symmetrically around the mean. Technically the gaussian distribution is unbounded. This means that you can get any value from - to +. However, due to limits that we have on computers we generally don’t show all the values up to +/- , but only up to a couple standard deviations past the mean on each side. The equation for the gaussian PDF is:

Below you can see how changing the mean and standard deviation changes the magenta distribution relative to the grey reference distribution. We plot both the PDF and the CDF (the integral of the PDF). There are a couple things to note. The area under the curve of the PDF will always equal 1. Changing the standard deviation decreases the likelihood of getting any value but increases the range of likely values you can get.

Source

mu = 0

std = 1

x = np.linspace(mu - std * 4, mu + 4 * std, num=400)

y = np.exp(-((x - mu) ** 2) / (2 * std**2)) / np.sqrt(2 * np.pi * std**2)

source = ColumnDataSource(

{

"x": x,

"y": y,

"yc": np.cumsum(y) * 0.020050125313283207,

}

)

pdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="PDF")

pline = pdf.line("x", "y", source=source, color="magenta")

pline1 = pdf.line(x, y, color="grey")

cdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="CDF")

cline = cdf.line("x", "yc", source=source, color="magenta")

cline1 = cdf.line(source.data["x"], source.data["yc"], color="grey")

mu = Slider(start=-10, end=10, value=0, step=0.5, title="Mu (mean)")

std = Slider(start=0.1, end=10, value=1, step=0.5, title="Sigma (std)")

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

source=source,

mu=mu,

std=std,

),

code="""

const arr = [];

const start = mu.value-std.value*4

const end = mu.value+std.value*4

const step = (end - start) / (400 - 1);

for (let i = 0; i < 400; i++) {

arr.push(start + step * i);

}

const temp_y = arr.map(x => {

const coefficient = 1 / Math.sqrt(2 * Math.PI * Math.pow(std.value, 2));

const exponent = -Math.pow((x - mu.value), 2) / (2 * Math.pow(std.value, 2));

return coefficient * Math.exp(exponent);

})

const cumsum = [temp_y[0]]

for (let i = 1; i < 400; i++) {

cumsum.push((cumsum[i-1] + temp_y[i]));

}

source.data.y = temp_y;

source.data.x = arr;

source.change.emit();

""",

)

mu.js_on_change("value", callback)

std.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(row(mu, std), row(pdf, cdf)))First we will start by looking at some of the data we previously collected.

Lognormal distribution¶

The lognormal distribution is a distribution where if you log transform the data you will get the normal distribution. If your data has a right skew (long tail to the right) your data may follow a lognormal distribution. You may ask why not just log transform the data? Log transforming means your data will no longer be in the same scale which makes downstream interpretations more complicated. The lognormal distribution is very common in biological sciences. Things like rates, lengths, concentrations and energies often follow a lognormal distribution. The lognormal distribution bounds are (0,+), The () brackets are exclusive which means that you can never have a 0 in the distribution since any log of 0 is undefined. The PDF of the lognormal distribution is:

Source

mu = 0

std = 1

x = np.linspace(0.000001, np.exp(mu) + 4 * np.exp(std), num=400)

y = np.exp(-((np.log(x) - mu) ** 2) / (2 * std**2)) / (

x * std * np.sqrt(2 * np.pi * std**2)

)

source = ColumnDataSource(

{

"x": x,

"y": y,

"yc": np.cumsum(y) * 0.020050125313283207,

}

)

pdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="PDF")

pline = pdf.line("x", "y", source=source, color="magenta")

pline1 = pdf.line(x, y, color="grey")

cdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="CDF")

cline = cdf.line("x", "yc", source=source, color="magenta")

cline1 = cdf.line(source.data["x"], source.data["yc"], color="grey")

mu = Slider(start=0, end=10, value=0, step=0.5, title="Mu (mean)")

std = Slider(start=0.25, end=10, value=1, step=0.25, title="Sigma (std)")

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

source=source,

mu=mu,

std=std,

),

code="""

const arr = [];

const start = 0.00001;

const end = Math.exp(mu.value)+Math.exp(std.value)*4;

const step = (end - start) / (400 - 1);

for (let i = 0; i < 400; i++) {

arr.push(start + step * i);

}

const temp_y = arr.map(x => {

const coefficient = 1 / (Math.sqrt(2 * Math.PI * Math.pow(std.value, 2))*x*std.value);

const exponent = -Math.pow((Math.log(x) - mu.value), 2) / (2 * Math.pow(std.value, 2));

return coefficient * Math.exp(exponent);

})

const cumsum = [temp_y[0]]

for (let i = 1; i < 400; i++) {

cumsum.push((cumsum[i-1] + temp_y[i]));

}

source.data.y = temp_y;

source.data.x = arr;

source.data.yx = cumsum;

source.change.emit();

""",

)

mu.js_on_change("value", callback)

std.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(row(mu, std), row(pdf, cdf)))Gamma distribution¶

The gamma distribution is another important distribution for neuroscience data. The gamma distribution is used to model waiting times and rates. A lot of data we collect are rates, such as mini or spike frequency. If your data has a right skew (long tail to the right) your data may follow a gamma distribution. Interestingly, gamma distributed variables often maximize the information content of a signal which is useful in the brain. The gamma distribution is the generalization the exponential, Erlang and chi-squared distribution. The gamma distribution is defined by a shape, , and scale, , parameter. Similar to the lognormal distribution the gamma distribution bounds are (0,+). The PDF of the gamma distribution is:

is the Gamma function is the factorial function that is generalized to complex numbers (except non-positive complex numbers)

You can also get the mean: and variance: of the distribution.

Source

shapes = [1.0, 1.25, 1.25, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.5]

scales = [2.0, 2.0, 3.0, 2.0, 2.0, 1.0, 1.0]

x = np.linspace(0, 20, num=400)

keys = []

glines = {}

cdflines = {}

gamma_fig = figure(height=250, width=350)

gamma_cdf = figure(height=250, width=350)

for i, j in zip(shapes, scales):

pdf = stats.gamma.pdf(x, i, scale=j)

cdf = stats.gamma.cdf(x, i, scale=j)

k = f"a={i} theta={j}"

keys.append(k)

glines[k] = gamma_fig.line(x, pdf, color="grey")

cdflines[k] = gamma_cdf.line(x, cdf, color="grey")

select = Select(title="Option:", value="a=1.0 theta=2.0", options=keys)

glines["a=1.0 theta=2.0"].glyph.line_color = "magenta"

glines["a=1.0 theta=2.0"].glyph.line_width = 3

cdflines["a=1.0 theta=2.0"].glyph.line_color = "magenta"

cdflines["a=1.0 theta=2.0"].glyph.line_width = 3

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

glines=glines,

cdflines=cdflines,

select=select,

),

code="""

for (let key in glines) {

if (select.value == key) {

glines[key].glyph.line_color = 'magenta';

cdflines[key].glyph.line_color = 'magenta';

glines[key].glyph.line_width = 3;

cdflines[key].glyph.line_width = 3;

}

else {

glines[key].glyph.line_color = 'grey';

cdflines[key].glyph.line_color = 'grey';

glines[key].glyph.line_width = 1;

cdflines[key].glyph.line_width = 1;

}

}

""",

)

select.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(select, row(gamma_fig, gamma_cdf)))Beta distribution¶

The beta distribution is used to model data that has finite intervals, and proportions and percentages. Some bounds values you might see in neuroscience are correlations (-1,1) and PPR (if you use the percentage formula and not the ratio). The beta distribution’s bound are (0,1) so if you have bounded data that is not between those you can transform it. The beta distribution is defined by a shape, , and scale, , parameter. The PDF of the beta distribution is:

is the Gamma function is the factorial function that is generalized to complex numbers (except non-positive complex numbers). The denominator of the PDF is a normalization factor to ensure the distribution has a total probability of 1.

One thing that you will notice is that the beta distribution can take on a wide range of shapes. This makes is very powerful for oddly shaped distributions. It can even even model normally distribution and uniformally distribution data when =

You can also get the mean: and variance: of the distribution.

Source

shapes = [0.5, 5, 1, 2, 5, 1.25, 1, 5]

scales = [0.5, 1, 3, 2, 2, 5, 1, 5]

x = np.linspace(0, 1, num=400)

keys = []

blines = {}

cdflines = {}

beta_fig = figure(height=250, width=350)

beta_cdf = figure(height=250, width=350)

for i, j in zip(shapes, scales):

pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x, i, j)

cdf = stats.beta.cdf(x, i, j)

k = f"a={i} b={j}"

keys.append(k)

blines[k] = beta_fig.line(x, pdf, color="grey")

cdflines[k] = beta_cdf.line(x, cdf, color="grey")

select = Select(title="Option:", value="a=0.5 b=0.5", options=keys)

blines["a=0.5 b=0.5"].glyph.line_color = "magenta"

blines["a=0.5 b=0.5"].glyph.line_width = 3

cdflines["a=0.5 b=0.5"].glyph.line_color = "magenta"

cdflines["a=0.5 b=0.5"].glyph.line_width = 3

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

blines=blines,

cdflines=cdflines,

select=select,

),

code="""

for (let key in blines) {

if (select.value == key) {

blines[key].glyph.line_color = 'magenta';

cdflines[key].glyph.line_color = 'magenta';

blines[key].glyph.line_width = 3;

cdflines[key].glyph.line_width = 3;

}

else {

blines[key].glyph.line_color = 'grey';

cdflines[key].glyph.line_color = 'grey';

blines[key].glyph.line_width = 1;

cdflines[key].glyph.line_width = 1;

}

}

""",

)

select.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(select, row(beta_fig, beta_cdf)))Poisson distribution¶

The Poisson distribution is a discete distribution used model the probability of a certain number of events occuring within a time frame thus it models the rate of events. The Poisson distribution assumes that each event is independent of each other. The Poisson distribution is similar to the gamma distribution kind of like the discrete cousin of the gamma distribution. The Poisson distribution has an important related feature called dispersion (technically other distributions also have this but is is particularly useful for the Poisson distribution) or the fano factor: , which is also related to the coefficient of variation: . The fano factor is often used to check the variability of a spike train, minis and any set of data that has events. The closer the fano factor is to 0, then the more predicable the process is, think of a cell spiking everytime at the trough of a 4 Hz sine wave. The farther you go above 1 the more clustered your events will be suggesting that there is some reason your events cluster (make sense for neurons that can fire spike trains). The Poisson PMF is defined by $ On the x-axis you have the number of events that could occur for each number of events that could occur you have probability on the y-axis. Since the Poisson distribution is a discrete distribution you actually get probabilities out instead of likelihoods. One thing to note is that the plot uses scatter instead of a line. This is to indicate that the Poisson distribution can only take integer values.

Source

lam = 1

k = np.arange(0, 21)

y = (lam**k * np.exp(-lam)) / np.array([math.factorial(i) for i in k])

source = ColumnDataSource({"k": k, "y": y, "yc": np.cumsum(y)})

pdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="PDF")

pline = pdf.scatter("k", "y", source=source, color="magenta")

pline1 = pdf.scatter(k, y, color="grey")

cdf = figure(height=250, width=350, title="CDF")

cline = cdf.scatter("k", "yc", source=source, color="magenta")

cline1 = cdf.scatter(source.data["k"], source.data["yc"], color="grey")

lam = Slider(start=0.5, end=10, value=1, step=0.25, title="Lambda")

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(

source=source,

lam=lam,

),

code="""

const arr = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 21; i++) {

let result = 1;

for (let k = 2; k <= i; k++) {

result *= k;

}

const val = ((lam.value**i)*(Math.exp(-1*lam.value)))/result;

arr.push(val);

}

const cumsum = [arr[0]]

for (let i = 1; i < 21; i++) {

cumsum.push((cumsum[i-1] + arr[i]));

}

source.data.y = arr;

source.data.yc = cumsum

source.change.emit();

""",

)

lam.js_on_change("value", callback)

show(column(row(lam), row(pdf, cdf)))Fitting your data to a distribution¶

In this next section we will look at how data fits to different distributions. Due to limitations of the format we will stick with IEI data however, I encourage to you modify the code below on either the other data we have or better yet on your own data. You should note that it is quite hard to accurately describe your data with distributions as you will see. Part of this is the limitation of the tools we have to fit a distribution to our data and that our data are messy due to measurement noise, recording conditions, etc. We will fit a gamma and lognormal distribution to the IEI data with and without a transform.

You will also notice that the gamma distribution does not fit very well with the untransformed data. You will also notice how the normal, lognormal and gamma distribution converge as the transform gets stronger. The biggest problem with IEI data is that it is tightly clusters around the mode and has a long tail to the right (right-skew). The mode can be estimated by looking at peak of the KDE. Many models assume some relationship between the mean and the variance of the data so the functions have limited types of shapes that they can support. For all the models that we used, the lognormal distribution is the best. This is probably because it is parameterized the same way as the normal distribution. Another thing to think about is that earlier we showed how we can model IEIs by randomly distributing events over time. Why does our data here not match that data? When we put TTX in the bath minis (mE/IPSCs, not sE/IPSCs) should be randomly distributed over time. One reason is that we cannot resolve mini events that are overlapping. This leads to a lognormal like distribution where we can occasionally resolve overlapping events and small amplitude events. Additionally, there are mini events that are smaller than the noise of the recording so we will miss those minis but it does not mean they do not exist. We have two factors which are simply limitations of the technique we are using which could change the distribution of the data that we collect.

Lastly, when Scipy fits data to a distribution it will modify the location of the distribution which usually does not occur when fitting regression models if the model does not explicitly contain a location parameter (of which the normal distribution is one of the few that explicity contain it). So if you want to run a regression model (t-test, ANOVAs included) you may need to shift your data to just above 0 to improve the fit if you are using a gamma, beta or lognormal distribution. Additionally, Scipy fits distributions using Maximum Likelihood Estimation. There are other methods such as Expectation Maximization and Bayesian statistics that can fit distributions.

Source

dist_data = df.loc[df["IEI (ms)"] > 0, "IEI (ms)"]

def fit_distributions(data):

dist_dict = {}

min_val = min(data)

max_val = max(data)

padding = (max_val - min_val) * 0.1 # Add 10% padding

grid_min = min_val - padding

grid_max = max_val + padding

grid_min = max(grid_min, 0)

positions = np.linspace(grid_min, grid_max, num=248)

kernel = stats.gaussian_kde(data)

y = kernel(positions)

dist_dict["kde_x"] = positions

dist_dict["kde_y"] = y

# Gaussian distribution fit

norm_vals = stats.norm.fit(data)

dist_dict["norm_x"] = np.linspace(1e-10, data.max() + 1e-10, 248)

dist_dict["norm_y"] = stats.norm.pdf(

dist_dict["norm_x"], loc=norm_vals[0], scale=norm_vals[1]

)

# Lognormal distribution fit

logvals = stats.lognorm.fit(data)

dist_dict["lognorm_x"] = np.linspace(1e-10, data.max() + 1e-10, 248)

dist_dict["lognorm_y"] = stats.lognorm.pdf(

dist_dict["lognorm_x"], logvals[0], loc=logvals[1], scale=logvals[2]

)

# Gamma distribution fit

gammavals = stats.gamma.fit(data)

dist_dict["gamma_x"] = np.linspace(1e-10, data.max() + 1e-10, 248)

dist_dict["gamma_y"] = stats.gamma.pdf(

dist_dict["lognorm_x"], gammavals[0], gammavals[1], gammavals[2]

)

return dist_dict

def create_fig(source, title):

fig = figure(height=250, width=400, title=title)

fig.line("lognorm_x", "lognorm_y", source=source, line_color="magenta")

fig.line("norm_x", "norm_y", source=source, line_color="orange")

fig.line("gamma_x", "gamma_y", source=source, line_color="blue")

fig.line("kde_x", "kde_y", source=source, line_color="black", line_width=3)

return fig

source = ColumnDataSource(fit_distributions(dist_data))

fig = create_fig(source, title="No transform")

sqrt_source = ColumnDataSource(fit_distributions(np.sqrt(dist_data)))

sqrt_fig = create_fig(sqrt_source, title="Sqrt")

log10_source = ColumnDataSource(fit_distributions(np.log10(dist_data)))

log10_fig = create_fig(log10_source, title="Log10")

legend = figure(y_range=(5, 5), height=250, width=400, title="Legend")

legend.line(

[0, 1], [0, 0], line_color="magenta", line_width=3, legend_label="lognormal"

)

legend.line([0, 1], [1, 1], line_color="orange", line_width=3, legend_label="normal")

legend.line([0, 1], [3, 3], line_color="blue", line_width=3, legend_label="gamma")

legend.line([0, 1], [4, 4], line_color="black", line_width=3, legend_label="kde")

legend.legend.location = "center"

show(column(row(fig, sqrt_fig), row(log10_fig, legend)))Based on the data you will see that the best fit for this IEI data is probably a lognormal distribution. If you want to run stats on the IEI data you will probably need to transform the data or use a lognormal distribution. This is true even though the IEIs should be exponentially distribution. Lastly, the lognormal distribution is interesting because it is everywhere. If you want to read more about the different neural processes that lognormally distributed you can read more in The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations Buzsáki & Mizuseki, 2014.

Describing a distribution¶

There several ways we can describe distributions: skew, kurtosis, location, and scale. We can also describe distributions in relation to each other such there the distributions exhibit the same variance, homoscedasticity, or differing variance heteroscedasticity. All of these features are important when analyzing your data.

Skew¶

Skew is how asymmetric the data is. We have seen some asymmetric distributions with the gamma and lognormal distribution. Skew also shifts the relationship between the mode, median and mean. Once your data skewed the most points will lie under the mode rather than the mean. The more skewed your data is, the more the mean starts to become affected by the extreme, outlier or influencer values. You can see below examples of different skew and how they affect the mean, median and mode.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(10,3), constrained_layout=True)

ax[0].set_title("Left skew")

i = np.exp(-1)

x = np.linspace(stats.lognorm.ppf(0.001, i), stats.lognorm.ppf(0.999, i), num=200)

y = stats.lognorm.pdf(x, i)

points = stats.lognorm.rvs(i, size=100)

_ = ax[0].plot(x, y, color="black")

_ = ax[0].axvline(x[y.argmax()], c="magenta")

_ = ax[0].axvline(np.median(points), c="blue")

_ = ax[0].axvline(np.mean(points), c="orange")

ax[2].set_title("Right skew")

_ = ax[2].plot(-x, y, color="black")

_ = ax[2].axvline(-x[y.argmax()], c="magenta")

_ = ax[2].axvline(-np.median(points), c="blue")

_ = ax[2].axvline(-np.mean(points), c="orange")

i = 0

x = np.linspace(stats.norm.ppf(0.001, i), stats.norm.ppf(0.999, i), num=200)

y = stats.norm.pdf(x, i)

points = stats.norm.rvs(i, size=100)

ax[1].set_title("No skew")

_ = ax[1].plot(x, y, color="black")

_ = ax[1].axvline(x[y.argmax()], c="magenta")

_ = ax[1].axvline(np.median(points), c="blue")

_ = ax[1].axvline(np.mean(points), c="orange")

Kurtosis¶

Kurtosis is the tailedness of the data, or how large the tails. While kurtosis is often seen with something called peakedness it is technically separate. The higher the kurtosis the more outliers you will get in your data. Kurtosis is often seen with changes in skew but is separate from skew.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(10,3))

ax[0].set_title("Negative kurtosis (platykurtosis)")

x = np.linspace(stats.uniform.ppf(0.001), stats.uniform.ppf(0.999), num=200)

y = stats.uniform.pdf(x)

_ = ax[0].plot(x, y)

x = np.linspace(stats.norm.ppf(0.001), stats.norm.ppf(0.999), num=200)

y = stats.norm.pdf(x)

ax[1].set_title("No kurtosis")

_ = ax[1].plot(x, y)

x = np.linspace(stats.laplace.ppf(0.001), stats.laplace.ppf(0.999), num=200)

y = stats.laplace.pdf(x)

_ = ax[2].plot(x,y)

_ = ax[2].set_title("Positive kurtosis (leptokurtosis)")

Heteroskedasticity¶

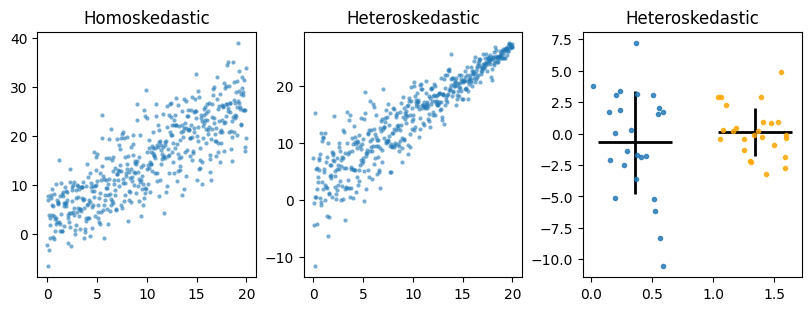

Heteroskedasticity means you have unequal variance (i.e. standard deviation) across groups (like genotype) or as x values increase or decrease. Heteroskedasticity violates one of the key assumptions of regression models, which is homogeniety of variances. Most basic tests such t-test and ANOVAs all assume homogeniety of variances since they use pooled estimates of variance and assume residuals come for a normal distribution with mean 0 and a fixed standard deviation. There are versions of t-test (Welch’s) and ANOVAs/linear regression (robust errors, weighted least squares) can control for heteroskedasticity which we will cover in the statistics chapter.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(8, 3), constrained_layout=True)

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

x = np.linspace(0, 20, num=500)

y = 1.2 * x + 3

rng.normal()

y1 = y + rng.normal(size=500, scale=5)

ax[0].plot(x, y1, ".", alpha=0.6, markeredgecolor="none")

ax[0].set_title("Homoskedastic")

temp = rng.normal(size=500, scale=5) * np.linspace(1, 0.1, num=500)

y2 = y + temp

ax[1].plot(x, y2, ".", alpha=0.6, markeredgecolor="none")

ax[1].set_title("Heteroskedastic")

y1 = rng.normal(size=25, scale=5)

x1 = rng.uniform(0, 1, size=25) * 0.6

y2 = rng.normal(size=25, scale=2)

x2 = rng.uniform(0, 1, size=25) * 0.6 + 1

ax[2].errorbar(np.mean(x1), np.mean(y1), xerr=0.3, yerr=np.std(y1), color="black", linewidth=2)

ax[2].plot(x1, y1, ".", alpha=0.8)

ax[2].errorbar(np.mean(x2), np.mean(y2), xerr=0.3, yerr=np.std(y2), color="black", linewidth=2)

ax[2].plot(x2, y2, ".", color="orange", alpha=0.8)

_ = ax[2].set_title("Heteroskedastic")

Hopefully at this point you have a better idea of what distributions are and how they represent our data.

- Buzsáki, G., & Mizuseki, K. (2014). The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(4), 264–278. 10.1038/nrn3687