Signals

Source

import json

import urllib

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from bokeh.io import output_notebook, show

from bokeh.layouts import column

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource, CustomJS, Slider

from bokeh.plotting import figure

from scipy import fft, signal

temp_path = (

"https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/LarsHenrikNelson/PatchClampHandbook/data/mepsc/"

)

with urllib.request.urlopen(temp_path + "1.json") as url:

temp = json.load(url)

data = temp["array"]-np.mean(temp["array"])

output_notebook()Signals are the transmission of data (see Wiki for more). This can be sounds, electrical signals (like electrophysiology), images, etc. Many signals that we are interested in are continuous, analog signals where as the signals we have analyzed in this book are discrete, quantized signals. This chapter will go into the basics of signal acquisition and how digital signals are represented. We will also cover some basic signal processing techniques such as the FFT and convolution. If you want more details I suggest reading The scientist and engineer’s guide to digital signal processing.

Electrophysiological signals¶

Electrophysiology is the analysis of electrical signals in biological systems and tissue. The electrophysiology analysis covered in this book is about the analysis of electrical signals in neurons collected through patch clamp electrophysiology. Other ways to study electrophysiology are sharp electrode recordings, EEG, EMG, LFP, single-unit recordings, multi-electrode arrays and magnetoencephalography (this one is indirect since it detects magnetic fields generated by electrochemical signals). A lot of the analysis and signal processing used in this book is applicable to all these other techniques but the end point is usually different.

Electrical signals in biological tissue are generated by charged ions (electrochemical) and not the flow of energy through electrons as in metal or semiconductors. In biological tissues we are detecting the flow of ions in and out cells or through axons. Ions in tend to have different concentrations inside and outside of cells. The difference of ions creates a potential or voltage difference. The voltage difference can change due to the flow ions through receptors which creates currents. The voltage differences and current are what we record in patch clamp.

Analog vs digital signals¶

Electrochemical signals are analog in that they are continuous and do not take on discrete values. However, most recording systems (if not all now days) are digital which means the analog signals need to be converted into a discrete-time and discrete-amplitude signal. Additionally, the analog signals we record are particularly small (pF, pA, mV) which means we usually need to amplify the signal, by changing the gain of the input, to see it. How this works is that you have analog circuitry that amplifies the signal and sends it into a analog to digital converter (ADC). To “read” the signal the DAC samples the analog signal at specified periods (sample rate). The sample rate determines how many times a second you sample the analog signal. A general rule of thumb is that you want to sample at 4x the slowest signal you want to analyze. You cannot analyze any signals above 1/2 your sample rate which is called the Nyquist limit. Aliasing, when low frequencies show up in your high frequency signals, can also be a problem when you get close to the Nyquist limit. When the DAC “reads” the signal it assigns the value it reads to the closest digital value which is usually a signed integer value (+ or - integer) and saves the value into a buffer, RAM or other storage. To convert the integer value back to the original signal value you just need to multiply is by gain (or inverse of the gain). The range of possible values that the digital signal can take is called the bit depth. The bit depth is usually something like 12 or 16 bits. The number of bits is related to the total number of discrete digital values a signal can be. 12 bits means that the signal can take on 2**12 different values. The bit depth is important for achieving good signal to noise ratio (i.e. the quality). While you can store digital data as float values, we typically store them as integers since they take up less space and give a large range of values. The gain setting is important because it can affect the signal to noise ratio (SNR) of your signal. Ideally you want to maximum the range of possible values your signal can take while also preventing clipping. Clipping is where the signal exceeds the range of digital values. Most modern electrophysiology systems will automatically set the gain so you should not have to worry about that. When your are injecting current the opposite happens. The digital to analog converter (DAC) outputs your signal generated by the computer and gain corrects it so that you get a continuous signal in the correct range.

Sample rate¶

The first thing we will talk about is sample rate. Sample rate determines what frequencies are in your signal, how filters are created, and the time scale of our recordings. In the example below you will find a plot that shows a sine wave at a 100 Hz sample rate. As you get close to 50 Hz you will notice your signal is not a pure sine wave any more but seems to be amplitude modulated. This is aliasing. Some aliasing can be prevented with filtering. The next thing you will notice is that as you go past 50 Hz the sine wave starts to decrease in frequency. This frequency “mirroring” is part of digital signals and shows up when running FFTs which we will go over later.

Source

time = 1 # Length of recording

fs = 100 # Sample rate

f0 = 4 # Current frequency

x = np.linspace(0, time, int(time * fs), endpoint=False)

y = np.sin(2 * np.pi * f0 * x) * (1 / f0)

source = ColumnDataSource(data=dict(x=x, y=y))

frequency = Slider(

title="Frequency at 100 Hz sample rate", value=4.0, start=0, end=100.0, step=1

)

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(source=source, frequency=frequency),

code="""

const y = source.data.x.map(xi => Math.sin(2 * Math.PI * frequency.value * xi) * (1 / frequency.value));

source.data.y = y;

source.change.emit();

""",

)

frequency.js_on_change("value", callback)

fig = figure(height=250, width=400)

fig.line("x", "y", source=source)

show(column(frequency, fig))Sample rate is also important for converting your signal indexes into times and vice versa. You will also see sample rate denoted as fs which you can think of as or . Where your frequency term is specified in the units of samples. If you have a set of times you can convert them to indices by int(index * fs) and from indices to time index / fs.

Frequency content of your signal¶

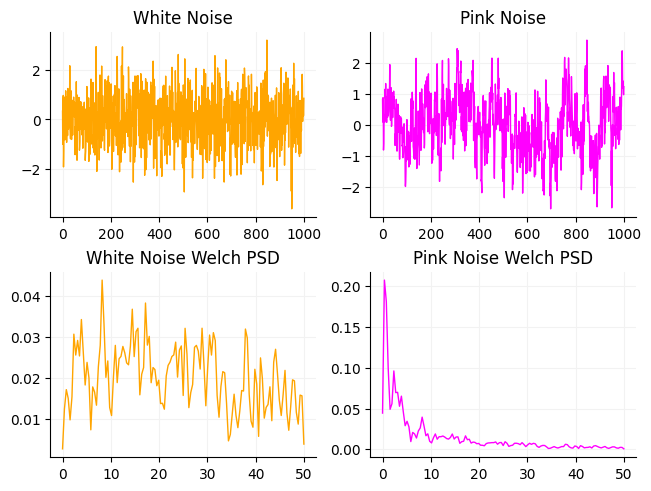

When you record a signal you typically see the time-domain representation of the signal. These signals contain frequency content since you time domain signal is collect of main different sinusoids (not sines or cosines but sinusoids) with different amplitudes and phases. Frequency is how fast the signal oscillates and phase is the portion of the wave that the signal is in (-pi/pi for troughs, 0 for peaks, -pi/2 or pi/2 for zero crossing). Frequency is easy to see when we have pure sinusoidal signal however, in the real world we typically do not have pure signals. The reason for this is noise and that the process generating our signal is likely not a pure 4 Hz sine generator. Digital signals has limited frequency content that depends on the sample rate that your signal is collected at as well saw above. Since our signals are not single frequencies our signals are actually made up of an infinite number of frequencies with different amplitudes and phases that change over time. How these frequencies are distributed depends on your signal. Generally electrophysiology data has a 1/f signal where low frequencies have higher power than high frequencies. What this means is that you get an exponential decrease in power with increasing frequency. Below is an example of white noise and pink noise. You have heard of these types of noise before. While each noise contains the same frequncies, the power of each of the frequencies is different. You can see that when the power of the different frequencies is different you get a different time domain signal. This gets to a fundamental idea that any signal can be recreated from a series of sine waves with different amplitudes and phases.

Source

def white_noise_array(N):

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

return rng.standard_normal(N)

def pink_noise_array(N):

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

X_white = fft.rfft(rng.standard_normal(N))

S = fft.rfftfreq(N)

S = 1 / np.where(S == 0, float("inf"), np.sqrt(S))

# Normalize S

S = S / np.sqrt(np.mean(S**2))

X_shaped = X_white * S

return fft.irfft(X_shaped)

wn = white_noise_array(1000)

wn = wn - wn.mean()

pn = pink_noise_array(1000)

pn = pn - pn.mean()

freq, wwelch = signal.welch(wn, fs=100)

freq, pwelch = signal.welch(pn, fs=100)

x = np.arange(1000)

source = ColumnDataSource({"x": np.arange(1000), "white": wn, "pink": pn})

source2 = ColumnDataSource({"wfft": wwelch, "pfft": pwelch, "freqs": freq})

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=2, constrained_layout=True)

ax = ax.flat

ax[0].set_title("White Noise")

ax[0].plot(x, wn, color="orange", linewidth=1)

ax[1].set_title("Pink Noise")

ax[1].plot(x, pn, color="magenta", linewidth=1)

ax[2].set_title("White Noise Welch PSD")

ax[2].plot(freq, wwelch, color="orange", linewidth=1)

ax[3].set_title("Pink Noise Welch PSD")

_ = ax[3].plot(freq, pwelch, color="magenta", linewidth=1)

for a in ax:

a.spines["right"].set_visible(False)

a.spines["top"].set_visible(False)

a.grid(axis='both', color='0.95')

Below you can see how two sine waves with different frequencies and phases interact.

time = 1 # Length of recording

fs = 100 # Sample rate

f0 = 4 # Current frequency

x = np.linspace(0, time, int(time * fs), endpoint=False)

y = np.sin(2 * np.pi * f0 * x) * (1 / f0)

y1 = np.sin(2 * np.pi * f0 * x) * (1 / f0)

source = ColumnDataSource(data=dict(x=x, y=y, y1=y1, y2=y+y1))

frequency = Slider(

title="Frequency", value=4.0, start=0, end=25.0, step=0.5

)

phase = Slider(

title="Phase", value=0, start=0, end=2, step=0.1

)

callback = CustomJS(

args=dict(source=source, frequency=frequency, phase=phase),

code="""

console.log(phase);

const y = source.data.x.map(xi => Math.sin(2 * Math.PI * frequency.value * xi + phase.value) * (1 / frequency.value));

const temp = y.map((val, index) => val + source.data.y[index]);

console.log(temp)

source.data.y1 = y;

source.data.y2 = temp;

source.change.emit();

""",

)

frequency.js_on_change("value", callback)

phase.js_on_change("value", callback)

fig = figure(height=250, width=400)

fig.line("x", "y", source=source, color="orange")

fig.line("x", "y1", source=source, color="magenta")

fig.line("x", "y2", source=source, color="black")

show(column(frequency, phase, fig))The FFT¶

To look at the frequency content of your signal you need to transform your signal using something called the Fourier Transform. The Fourier Transform transforms your signal from the time domain to the frequency domain (big simplification since it can be used for more than this). You might have seen something called the FFT. The FFT is the Fast Fourier Transform and is the speedy digital version of the Fourier Transform that specifically computes the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT). The FFT is one the core digital signal processing algorithms. Essentially the FFT decomposes your signal into set of component complex frequencies, sine and cosine frequencies. The frequencies contain a real portion which is the sine frequency component and the imaginary portion which is the cosine component. Note that your signal does not contain sine and cosine signals, just that your signal can be decomposed into sine and cosine signals. You can take the absolute value of the complex frequencies to get the amplitude or power of the specific frequenies in your signal. You can compute the angle (remember how sine and cosine relate to the unit circle) of each of your frequencies to see the phase of the frequency. The FFT also outputs negative frequencies. Negative frequencies for any signal that contains only real values, such as electrophysiological signals are just the frequencies above the Nyquist limit. These frequencies just mirror the frequencies below the Nyquist limit just as we saw with the sine wave frequency and sample rate interaction example above.

There are many variants of the FFT algorithm. Some focus on multithreading, others focus on signals whose length is a prime number (since this is traditionally very slow), GPU versions (like in Pytorch), and others focus on all around performance (Scipy). In Python you can access a decent version through the Scipy FFT module. You can get a very fast version called pyFFTW which is a wrapper around FFTW (it is very fast) or a GPU based version in Pytorch or Tensorflow.

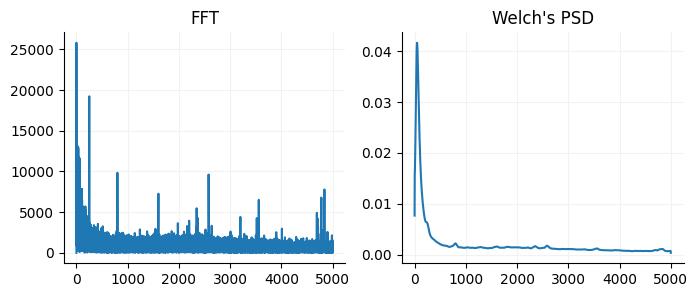

In addition to the general FFT algorithm in Python there are different ways to input and modify the output of your data that can improve the ability to interpret the frequency data. The most common way to pre- and post-process your data when looking at power is to use a Welch’s PSD. Welch’s method takes consecutive chunks, windows the chunk, takes the FFT of the chunk then averages all the FFTs together and finally takes the absolute value.

Another, useful feature of the FFT is that you can increase the frequency resolution of your FFT by zero-padding your data (just add zeros to the end). We can do this because the FFT outputs an array that is the same size as is put in. This can be useful if you have a shorter signal but want a higher resolution sampling of frequencies. It is important to note that if you zero-pad your time domain signal run the FFT and then reverse the FFT you will not get an upsampled signal. Scipy’s FFT functions and Welch have a keyword argument n and nfft respectively which allows to you specify the number of samples you want in your FFT. However, zero padding does not get around the inherent limits introduced by the length of your signal. For example to assess the 4 Hz frequency you need a signal that is a least 0.25 seconds long otherwise you will not get a full cycle of any 4 Hz frequency that is present.

fs = 10000

freq_fft = fft.rfftfreq(data.size, 1/fs)

data_fft = np.abs(fft.rfft(data))

freq_welch, data_welch = signal.welch(data, fs=fs, nfft=4048, noverlap=248)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2, figsize=(8,3))

ax[0].plot(freq_fft, data_fft)

ax[0].set_title("FFT")

ax[1].plot(freq_welch, data_welch)

ax[1].set_title("Welch's PSD")

for i in ax:

i.spines["right"].set_visible(False)

i.spines["top"].set_visible(False)

i.grid(axis='both', color='0.95')

If you want to get the power for a specific frequency band you can sum the values of the FFT frequencies you are interested in. For the FFT you may need to zero-pad your signal to get enough frequencies in the range you are interested in if your signal is short.

print("Theta power: ", np.sum(data_welch[(freq_welch >= 3) & (freq_welch <= 10)]))

print("Gamma power: ", np.sum(data_welch[(freq_welch >= 30) & (freq_welch <= 80)]))Theta power: 0.05147223946655652

Gamma power: 0.7566028898829424

What do we use the FFT for?¶

The FFT is extremely useful for signal processing beyond just looking frequency content. The FFT allows us to do convolution, or deconvolution like we used to find mEPSCs, very quickly when we have two long signals by changing convolution into multiplication (which is simpler) and deconvolution into division. We can use the FFT to look at phase locking between trials or signals. We can use the FFT to create filters. Which we will talk about more in the next chapter. You can use the FFT to remove stripes from images or videos (which are just a collection of images). Some specific versions of the FFT are used for JPEG and MPEG encoding/decoding. You can use the FFT to upsample signals by zero padding the FFT.

Conclusion¶

In this chapter we learned a bit about signals. How we get from analog to digital and some properties of digital signals. In the next chapter we will learn about signal processing techniques such as convolution, correlation (template matching, reverse convolution), filtering, peak finding. Some these techniques are covered in the analysis tutorials but we will cover some tips on how to best use those techniques.