Current clamp

Current clamp recordings are one of the most common patch-clamp experiment. Current clamp experiments allow you to get the active parameters of cells. Namely gain, rheobase and spike threshold. Current clamp recordings typically use stepped currrent injections or ramps and you are investigating the voltage change due to the current injection and whether and how the cell spikes. The current clamp chapter is divide into two parts. The first part is a basic analysis and covers what features we look for and why they are important. The second part will delve much deeper in relationships between spike features and cover differences between a few cell types; pyramidal cells, spiny projection neurons and parvalbumin interneurons.

Experimental considerations for current clamp recordings¶

Internal and external solutions¶

You will need to a standard ACSF for recording. Many labs mantain the ACSF at physiological temperatures which is considered ~32°C however you can record at room temperature but, reviewers may not like it. I recommend recording at 30-32°C. You can include drugs in the bath to block synaptic activity but do not need to include these. If you are having a lot of recurrent input that is driving spikes, depolarizations or hyperpolarizations in your cells if may be good to include some drugs to block synpatic currents. The one problem with blocking synaptic currents there can be homestatic changes in cell functin due to changes in or lack of synaptic input. These are considerations you need to consider. I would recommend starting without any drugs in the bath to keep it simple.

To use a holding current or not¶

One thing to consider is whether you should inject a slow holding current to bring the cell to a specific resting potential value. Some labs inject current to hold the cell at around -70mV or the cell type preferred membrane voltage and run their current pulses or ramps based on that holding current. There other labs that do not inject any holding current and even argue against injecting any holding current. One thing to consider is how you are measuring membrane resistance. HCN channels and other voltage gated channels opening and closing changes with membrane voltage. So if have two cells have a different then the membrane resistance values you get are going to be different simply because they are at different due to differences in the number of voltage-gated that are open or closed. Another question is whether rheobase is the current it takes to get a cell to spike from a specific membrane voltage or from where the resting membrane potential is? Here is an example to consider. It takes 50 pA to get a layer 5 pyramidal in a WT mouse to fire an action potential from -70 mV and in a knockout mouse it takes 100 pA. However, the WT mouse cells sits a -70 mV at baseline where as knockout mouse sits as -60 mV. What if there is no difference in the rheobase current? What if there is a difference in rheobase current but no difference in resting membrane potential?

Another factor to consider is that some cells, such as dopaminergic cells, glutamateric cells and interneurons in the VTA spontaneously spike in slices, even with high Mg+ (2 mM) and even after the high K+ solution perfuses the cell in whole cell setup. To test rheobase you have to inject some current so you will likely need to at least hold them below the spike threshold. I have read that you cannot actually test rheobase in these cells because they are spontaneously firing. Instead you can see how much current it takes to suppress the spontaneous firing. On the other hand, many internals used for current clamp experiments primarily composed of K+ which I have found spontaneous firing to cease in many of these cells upon break in so it may not be a problem.

Steps vs ramps¶

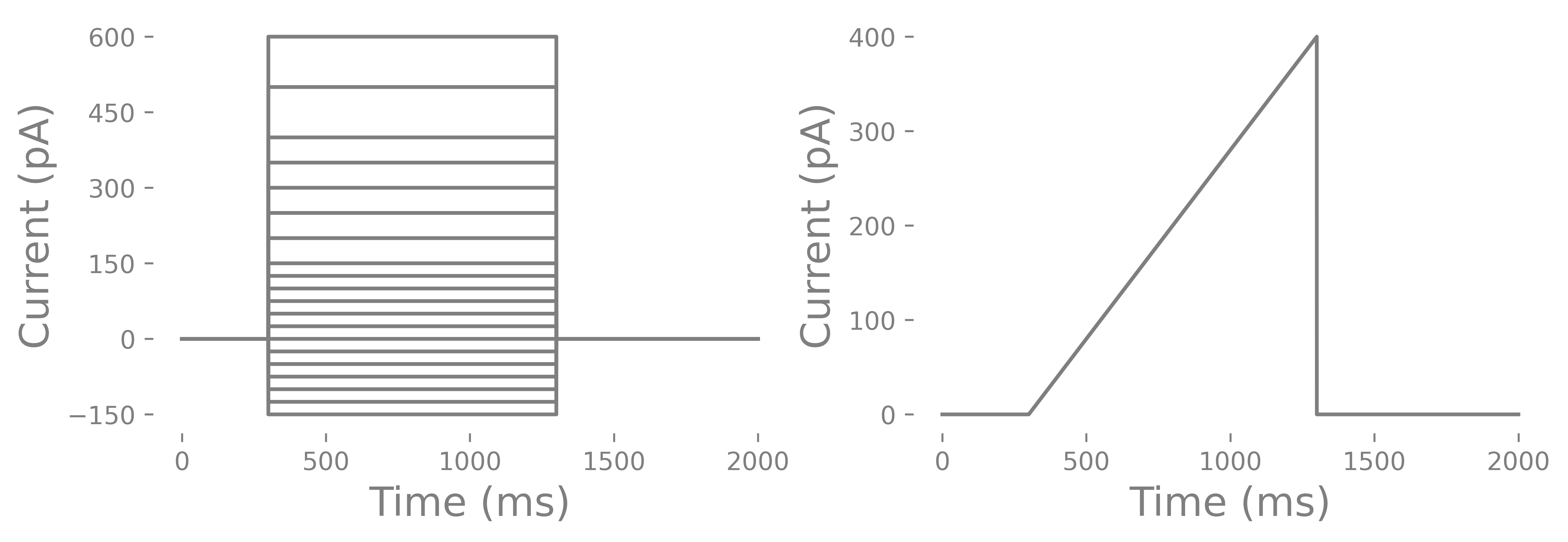

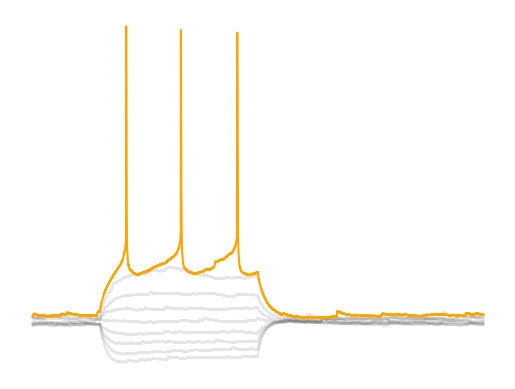

As mentioned in the beginning, you can record stepped currents or ramps. Stepped currents are the most common. Usually there are negative and positive steps. The negative steps can go as low as -150 to -200 pA and positive currents can as high as 600 pA (some interneurons have a very high rheobase), Steps can be irregular or regularly spaced. One problem with ramps is that some cells have depolarization block and may not spike during a ramp but will during a set of stepped pulses. Depolarization block is the inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels due to long membrane depolarizations that does not elicit any spikes. There are conditions, such as epilepsy, where depolarization block may actually be a feature of the altered cell physiology and you could use the ramp to test whether this occurs. Below you can see and example current injection cycle and a ramp.

How do you determine the length of a current injection? You can do short 3 ms long pulses or long 1000 ms long pulses. You can use short and steep ramps or slow and long ramps. You all of these and compare each. However, most commonly you will find that labs use a 500-1000 ms current injection. This is considered infinitely long. The reason has to do with rheobase and a related feature call chronaxie which I will explain below. You may also notice that in some cells the membrane potential slowly increases after the initial current injection until the cell spikes where as other cells, particularly PV interneurons, do not have an increase in membrane potential. Lastly you should consider whether or not you want to run multiple cycles of the pulses. Some labs only run one cycle with small steps to save time. Other labs run several cycles/epochs and average the values from each of the cycles/epochs. One thing I will point out is that neurons are probablistic and priors can changes how a neurons is likely to function. Some would argument that a cycle of current injections will alter the function of a neuron. However, the internal we use tends to hyperpolarize cells and we put in Ca+ chelator’s like EGTA. Others will argue that because neurons are probablistic you need to to run several cycles to get the central tendency of a particular characteristic (like rheobase) of a cell. The analysis I will go through uses the multiple cycle approach.

What is ...?¶

This next section talks about some fundamental features of neurons. These are things you should know even if you want to skip the analysis sections of the book.

...rheobase?¶

Rheobase is one the key parameters researchers extract from current clamp data. Rheobase is consider the minimal current it takes to get a cell to fire an action potential when using an infinite duration current injection and is related to something called chronaxie @irnich_terms_2010, Irnich, 1980. Rheobase is considered the input gain of a cell; how reactive a cell is to excitatory input. Rheobase as a measure is based off a curve called the Lapicque hyperbolic strength-duration curve where strength is the strength of the current injection and duration is the duration of the current injection. This curve is a decaying exponetial curve and rheobase is essentially the steady state of the duration if the stimulus was infinitely long. Earlier I went over how you could deal with cells that are spontaneously spiking. I have heard some arguments that you cannot even test rheobase in these cells types. If you do not want to inject current to hold the cell at -70 or another membrane voltage then you can specify rheobase as the minimum current needed to suppress spontaneous firing. This might make sense for cells that receive very little excitatory input but a lot of inhibitory input (like dopaminergic cells).

...membrane resistance?¶

Membrane resistance is the resistance of the membrane to a current. Resistance is determined by the number of ion channels that are open and the membrane composition. Membrane resistance is not linear over current injection amplitudes. The change in membrane voltage is the voltage difference between the baseline and the voltage during the current injection. Any resistor will cause a voltage drop you can measure resistance using . We always measure the voltage difference across an element. One thing to be aware of is that membrane resistance changes with membrane voltage, that means injecting a slow holding current to hold a cell at a specific vs letting the cell sit a can change how the membrane resistance is measured since ion channel opening and closing depends on the membrane voltage. The ways you may see membrane resistance measured are:

Repeated measures ANOVA looking at delta V vs current injection

Repeated measures ANOVA looking a instantaneous membrane resistance vs current injection.

Slope of the linear regression using only: the negative current injections, the positive and negative current injections, or the rectified current injections (absolute value of current and voltage).

...spike threshold?¶

Spike threshold is the voltage threshold at which a spike will occur. This point is called a bifurcation point where there is change in the functional properties of a neuron. This bifurcation point and how it relates to the function of a neuron are studied in the field of dynamical systems. The spike threshold is a not a fixed threshold. It depends on the previous membrane voltage and the change (dV/dt) in membrane voltage. For example, PV interneurons typically do not spike when using ramp injections due to depolarization block. PV interneurons need a large and sudden (i.e highly synchronous) synpatic/current input. Previous spiking activity also changes the spike threshold of a neuron as we will see in part 2 of the current clamp analysis. The flexibility of the spike threshold is a way for neurons to increase or decrease synchronization, feature selectivity, gain, etc. on the fly.

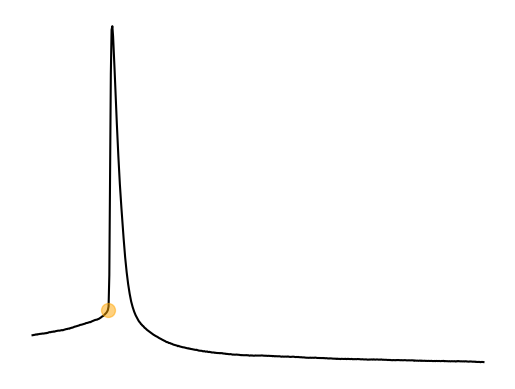

...the afterhyperpolarization (AHP)?¶

The AHP is the period in which a neuron cannot fire another action potential. This occurs due to densisitization of voltage-gated sodium channels. The AHP generally starts when the voltage drops below the spike threshold. The AHP occurs due to the activation of fast and slow K+ channels. The are several ways you will see the AHP analyzed. One is the maximum (or really the minimum) voltage the AHP hits. Another is the difference the maximum AHP and the spike threshold. This value can be affected by changes in the spike threshold so take care when interpreting it. Lastly, there is the mean/median value or slope of specific segments of the AHP that occur afte the AHP has reached is maximum value. The last measure is supposably allows you to measure effects of slow and fast K+ channels on the AHP. The minimum length of the AHP is important because it tells you how long a cell takes to recover before being able to spike again. This “recovery” time is partly measured by the time between spikes, the inter-event interval. The AHP can also be very different between cell types. Some cells like PV interneurons have incredilibly large but short AHPs where as pyramidal cells have smaller but long AHPs.

...the FI curve?¶

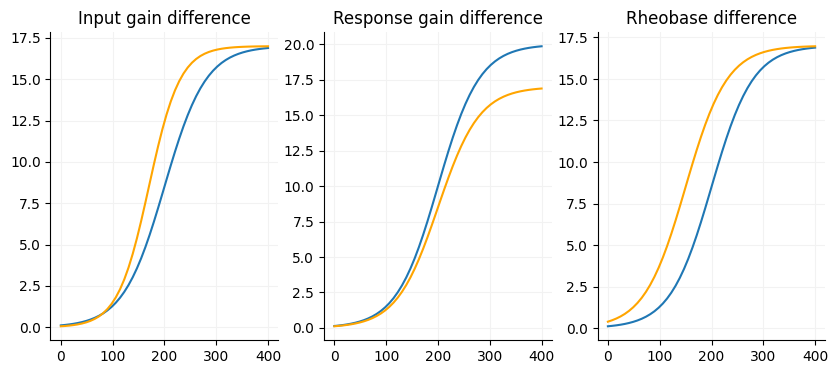

The FI curve is the input-output curve of a cell and allows you to inspect the different types of gain changes that may occur. You get this by plotting the current injected into the cell on the x-axis and the spike frequency of the cell on the y-axis. The plotting alone does not get you much other than a visualization of how the cell responds to current injections. You can analyze curve by fitting with a sigmoid function to get the additive/subtractive gain (rheobase), input gain (slope) and output gain (maximum firing rate). You can also analyze the FI curve by running a repeated measure ANOVA however, it is harder to interpret the specific features of the curve this way.

Understanding gain¶

A core aspect of the FI if there are any gain differences between your conditions. There are three factors we are interested in with the FI curve (slope, max firing rate and current offset) and one nusciance factor (voltage offset).

Slope: The input gain of a cell, slope of the linear portion of the curve.

Maximum firing rate: Output gain, the response gain of a cell.

Current offset: Additive/subtractive gain, pretty much just rheobase but can affected by the slope.

Voltage offset: This is usually close to zero and consider an unimportant factor for FI curves.

If you want to learn more about gain I would recommend looking at Ferguson and Cardin, 2020 Ferguson & Cardin, 2020.

...the firing rate?¶

The firing rate is the number spikes divided by the time of the current injection. If you use a one second current injection this is just the number of spikes. The firing rate on its own is not hugely important but is important for creating the FI curve.

...voltage sag?¶

Voltage sag during a hyperpolarizing current injection are caused by Ih currents which are due to K+ and Na+ ions flowing through hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels. Voltage sag is most prominent in cells that have HCN cells close to the cell body. Axon and dendritic HCN channels cause less sag. HCN channels help maintain a more depolarized resting membrane potential and can also stabilize the membrane potential so that larger amounts of synaptic input are needed to get the neuron to fire. This function is helpful for pacemaking cells. HCN channels can be expressed on spines, dendrites, cell bodies and axons. HCN channels have a reversal potential around -50 to -20 mV. HCN channels are opened by hyperpolarization below -40 to -60 mV and closed by depolarization. Once the HCN channels are open they will remain open creating an inward current until closed. HCN channels are a tetrameric protein with 4 subunit isoforms, 1-4. These subunits have differences in activation speed where activation speed fast to slowest 1 → 2 → 3 → 4. cAMP can also allow HCN channels to open faster and at more depolarized levels where sensitivity is most to least 4 → 2 → 1 → 3. Lastly HCN channel opening is faster at more negative voltages with voltage sensitivity being different among the channels. One prominent cell type that has very large HCN currents are midbrain dopaminergic neurons. When HCN channels are expressed on the axon, such as in PV interneurons, the HCN channels reduces the effects of hyperpolarizaton thus facilitating fast spiking. When HCN channels are expressed in the spines and dendrites they may help set the level of excitatory input needed to drive an action potential. The sag that we analyze is the HCN channel opening and depolarizing the cell to return the cell to its resting membrane potential.

...membrane time constant?¶

The membrane time constant is the time is takes for the membrane to get a steady state voltage before or after a small current injection. The time constant can determine the resonant property of a neuron, the preferred frequency at which the neuronal membrane oscillates. The membrane acts as a lowpass filter. If you neuron has Ih currents then the membrane acts more as a bandpass filter (low- and highpass filter combined). You can measure the time constant by finding the time at which the voltage gets to ~63% of its steady state voltage. If you have voltage sag this measure is pretty hard to measure in current clamp. The membrane time constant is also used to calculate the capacitance in voltage clamp when running a test pulse.

- Irnich, W. (1980). The Chronaxie Time and Its Practical Importance. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 3(3), 292–301. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1980.tb05236.x

- Ferguson, K. A., & Cardin, J. A. (2020). Mechanisms underlying gain modulation in the cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 21(2), 80–92. 10.1038/s41583-019-0253-y